INCLUSIVE EDUCATION FOR ALL #27

3 August 2022 by Chris Barnes, Inclusive Education Officer, Down Syndrome International

Head teachers and school leaders who were interviewed and contacted for this campaign understandably tended to focus on wider issues, and requirements of the school, rather than commenting on individual or cohort-based examples of inclusive education. When probed on the requirements for a more inclusive school offer, head teachers unvaryingly say ‘more money, please’ referring to the lack of real, ring-fenced funding usable for additional staff where needed. Several secondary headteachers said they would unquestionably accept all children, if they felt they could offer them a meaningful experience, and not just a physical place in the buildings – as could be the case under the current system of SEND support in the UK.

It is difficult to speak with authority in the presence of head teachers with decades of experience in school management, and I often felt decidedly unqualified to query their judgment, or comment on inclusive practice. Even so, most agreed that ‘inclusive education’ is indisputably the way forward and more must be done to bring about change, from the top. When I countered with, ‘Can inclusive education be brought about from any starting point in the system?’ this was argued with points:

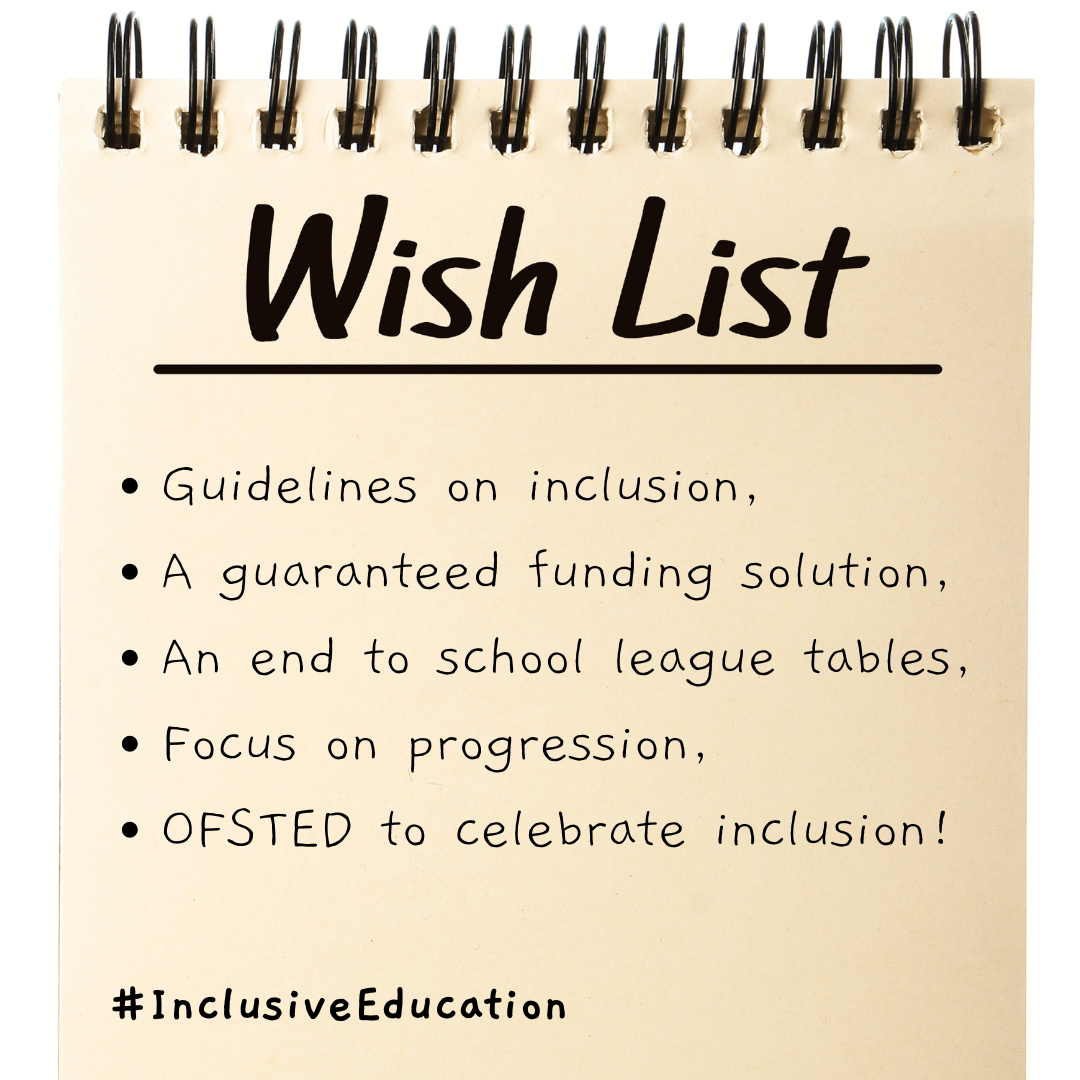

- UK schools are currently working with ambiguous guidelines on a definition of inclusion.

- Poor and unfairly distributed (debatable) funding and resource.

- League tables based on academic results.

- Demands on class teachers have never been higher with a greater proportion of children with additional needs in mainstream classes.

- Ofsted inspections not weighted heavily on inclusion.

In summary, leaders probably require much clearer statutory, and mandatory, guidelines on inclusion – and what that means for local children with intellectual disabilities who wish to be educated in a mainstream setting. Leaders probably require a streamlined, and guaranteed, funding solution to give them confidence in enrolling more learners with intellectual disabilities; that they will be adequately supported in line with EHCP/IEP requirements. For more school leaders to get on board with ‘inclusive education’ they require an end to, or change to the system of, school league tables and published results. Schools are businesses, and a lack of demand due to a drop in perceived standards (based on average results) is a no-go for too many head teachers desperate to maintain their position and be successful. School leaders require overall average points progress to consider and account for learners with SEND more efficiently as the current system is off-putting; learners with intellectual disabilities are perceived by many school leaders to ‘drag-down’ results. As long as academic results remain high on the priority list for what schools are reported on, inclusion may never take off in the UK. Head teachers require Ofsted to celebrate and give more attention to schools that take inclusion seriously.

For many school leaders to take the idea of inclusive education seriously, or begin to earnestly implement its values, the UK education system must prioritise and value the inclusion of children with disabilities (including intellectual disabilities) rather than seeking ways of providing ‘additional support,’ within a ‘mainstream’ provision. It is commonplace for school leaders to battle with, struggle, and languish in the UK SEND system (of funding and accountability) while at the same time aspiring for ‘high’ achievements of attainment and progress – with which to be reported on, and published. It is no surprise that the vast majority of head teachers prioritise the latter.

Some maverick school leaders outwardly embrace a more inclusive ethos, over and above other things, and should rightly be celebrated for doing so. Many people believe that, among many other things, school leaders need to be given clear, un-ambiguous guidelines on inclusion – that give no room for interpretation/misinterpretation. This is, of course, a matter for debate. School leaders require well-trained, forward-thinking, and hard-working staff to implement radical inclusion policies. This can’t, however, be another job on an already too long list – something has to give way to inclusion. School leaders, perhaps mostly, need a financial system that supports, and the financial security to invest in, inclusive education.

Next week: ‘How can leaders be inclusive role models?’