by Emily Seager

It is a well-known fact that children with Down syndrome have difficulties with acquiring language. We know also that language development is supported by other skills such as the child’s general cognitive development, their ability to extract words from the language they hear around them, and also their immediate social context and the way caregivers interact with the child. Early social communication skills include eye contact, gestures and the ability to share points of interest with others (joint attention). For example, a mother and child may be looking at a toy together at the same time. There are two types of joint attention – initiating and responding to joint attention. Initiating joint attention involves using gestures and/or eye gaze to direct the attention of another person, e.g. if a child pointed out the window to show their parent an aeroplane. Responding to joint attention is following the eye gaze/gesture of another person. So for example, when a parent shows a toy to the child and invites them to look at it and the child looks at the toy.

Previous research from members of our team found that the ability to respond to joint attention at 18-21 months (following the point/ focus of another person) significantly predicted language outcomes at 30-35 months in a group of infants with Down syndrome. Based on this finding, we wanted to trial an intervention that targeted responding to joint attention at 18-21 months to see if this would lead to better language skills at 30-35 months in infants with Down syndrome

Initially, we completed a literature search to find out more about if there are already interventions which aim to improve responding to joint attention and if any of these interventions had been used with children with Down syndrome. Our search found that an intervention targeting responding to joint attention had not previously been used with children with Down syndrome but many attempts had been made for children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). We decided to adapt an intervention that had previously been used with children with ASD.

Participants were recruited through local charities and support groups as well as by putting an advert on the Down Syndrome Association’s website. Sixteen families agreed to participate in the research study and came from many counties across the UK including Berkshire, Gloucestershire, Hertfordshire, Essex and Suffolk.

Before the intervention started, each child completed various standardised tests to measure their non-verbal abilities, joint attention and their understanding of language as well as their language production. The intervention lasted for 10 weeks and each participant received one intervention session per week from a researcher (this lasted about 30 mins) and parents completed ‘homework tasks’ three times per week at home. The parents were given a manual to help them support their child at home.

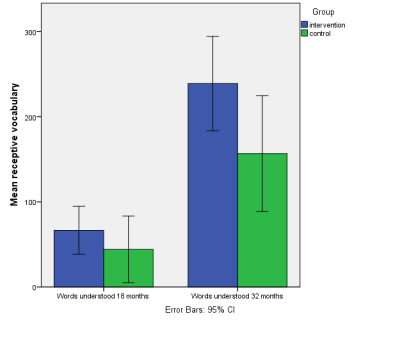

The infants were then re-tested directly after the intervention had finished, and again 3 months later (aged 24-30 months) and then again 6 months later (aged 30-35 months). When participants were assessed at the two follow up assessments their scores were compared to a group of children with Down syndrome who had not received the intervention. There were no differences between the intervention and control group for language/vocabulary scores when assessed at 24-29 months. However, a significant difference was found for receptive vocabulary (how many words the children were reported to understand) when they were assessed at 30-35 months. Those in the intervention group were reported to understand significantly more words than the children in the control group. See the graph below which shows that the children who had had the intervention, were reported to understand on average about 239 words a year after the intervention had finished whereas the children in the control group were reported to understand on average 133words.

After the intervention parents were asked to give feedback regarding the intervention. One-hundred percent said that they were extremely satisfied with the intervention and that they had noticed changes in their child’s joint attention abilities. Seventy-seven percent felt that their child’s speech and language had improved as a result of the intervention and 92% had noticed improvements in other areas of development e.g. in their child’s sustained attention. Finally, 92% of parents reported that they had changed how they were communicating with their child.

In conclusion, it appears that an intervention which aims to improve responding to joint attention is feasible for this client group and in this form. The intervention may have helped to accelerate responding to joint attention abilities and this may have had a cascading effect on receptive vocabulary capabilities. Future research should aim to include a larger cohort of children and use a randomised control trial design. This will ensure that the effects observed are due to the intervention and not because of spontaneous development.

Emily Seager is a PhD student at the University of Reading. Prior to her PhD Emily has worked on various projects assessing language using screening measures for preschool children.

Emily Seager is a PhD student at the University of Reading. Prior to her PhD Emily has worked on various projects assessing language using screening measures for preschool children.